by Krystal DiFronzo

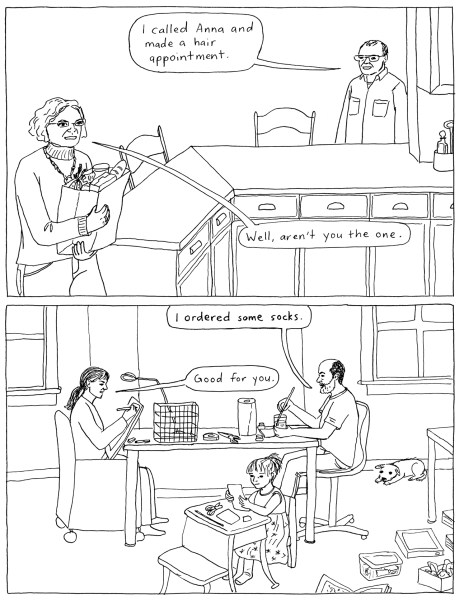

Keiler Roberts writes beautiful and frank auto-biographical comics about the complexities of her life as a teacher, artist, and mother. I got a chance to talk to her about her practice and her new book Sunburning, published by Koyama Press, that will be debuting next weekend at the Toronto Comics Art Festival.

Krystal DiFronzo: The longer stories in Sunburning mostly tackle your experience with various medical conditions. These range from an undiagnosed nerve condition and bipolar disorder to miscarriage. I’m curious as someone who has also tried to draw comics about their own traumatic medical issues, when did you feel was the best time to write about it? Have you been keeping notes and writing about some of these moments since they’ve happened or did you start to write about them specifically for this book?

Keiler Roberts: I wrote about those things at varying lengths of times after they happened. Bipolar disorder and the unrelated illusions and hallucinations are ongoing, but I don’t write about them during bad spells. There are great stretches of time when I get to be a “normal,” healthy person. It took about six years before I was able to describe the miscarriage in a way I was satisfied with. I have several longer, gorier versions. Time makes it easier for me to edit. When I’m very close to a rough experience I know I’m looking for something extra – attention, sympathy, or just wanting people to be aware of some part of me. At some point it changes, and I’m just trying to tell an interesting story. It happens to be mine, but I no longer need people to connect to me because of it. I hope they connect to the comic. I have to move past the point where I feel competitive, past the illusion that my miscarriage was the worst, that my post-partum depression was deeper and darker than anyone else’s. I know enough about other people to realize I’ve never had it the worst. I do take notes while events are happening, but I don’t always look at them when I’m making the comics. Journaling itself has a way of making certain memories stick.

KD: I’ve always found your pacing dynamic and this book is a great example of it. Some of the bits are one page snapshots while others develop into fully realized memories or mini-memoirs. There’s no dividing line between them, no titling to alert the reader immediately that one chapter has ended while another has begun. It connects all the stories in a way that feels most alike actual memory and thought. One moment you focus on a trauma and another moment your daughter, Xia, is saying some genius line like, “My tummy is horrified.” This feels very deliberate, how do you go about planning your books?

KR: Thank you! When I’m writing individual stories, I don’t know where they’ll be located in a book. I lay them all out on the floor and find an order that creates an emotional line that I like. I’m drawn to contrast and inconsistency. Maybe it’s the effect of bipolar rapid cycling on my personality, or maybe it’s just that jokes are funnier when they’re paired with something dark.

The themes that emerge aren’t planned before I begin. I didn’t set out to write so many stories with a medical component. I’d like to write more about my close friends and my teaching job because they are huge parts of my life that make only brief appearances in the book. This is where the line exists that separates my stories from my life, though. Powdered Milk has never been a totally accurate picture of my life. It’s all honest and true, but so much is excluded. It might just be about timing, though. I finally wrote Xia’s birth story, which wasn’t traumatic at all. I can’t predict which events will turn into comics, or when.

KD: What type of work were you doing prior to comics? What drew you to the medium? Who was the first cartoonist you read that really clicked with your sensibilities?

KR: I painted for many years – mainly loose photorealism of my own snapshots of friends, pets, and food. I started doing some illustration, thinking I’d like to make children’s books because I loved text and reproduced images. After pursuing that for a while I decided to quit art and make clothes. I started a blog-documented project of replacing my whole wardrobe with (mainly terrible) things I sewed and knit myself. Three years into that, I started another blog that paired illustrations with excerpts from my journal. All of this work, including the paintings, was autobiographical in some way. I was oblivious to alternative comics until I took a class with Aaron Renier called Graphic Narrative at DePaul in 2009. The first cartoonist that really opened my eyes was Gabrielle Bell. Her work changed my world. Everything I love about art existed within comics, and she was doing it.

KD: You’ve exhibited in two shows recently, a group show titled Mirror Face at Cleve Carney Gallery with Christa Donner and Sarah McEneaney and a solo show at The Naughton Gallery at Queen’s University in Belfast. How do you feel about taking comic pages out of context and displaying them in a gallery setting? How do you approach the challenge of displaying a printed comic alongside more traditional painting and installation work? Do you think anything is gained or lost in this translation?

KR: The pressure that I’d associated with museum and gallery shows was completely absent when showing comics. The curators of those shows, Ben Crothers (The Naughton Gallery) and Justin Witte (Cleve Carney) did all of the work and planning for how to display the pages. I dislike the care that precious objects require, but I’m happy to have my work in that setting. My work is better suited to museums or galleries than many comics because the stories are contained in short pieces and can be read in any order. The content isn’t sacrificed. Some people make beautiful pages that are worth seeing out of narrative context, just for their visual sake. My work doesn’t look that much different from the reproductions, and lacks the visual flair of a painting, or anything in color, or even the richness of a line drawing made with India ink. It is a different experience taking in something very personal and possibly emotional in a public space. I can only recall one work of gallery art that disturbed me into leaving, and one that made me cry. I think if anything is lost in translation, it’s the loss of privacy of the viewer, and maybe their willingness to participate emotionally.

KD: Your work has been prominently auto-biographical. You touch on some of the possible issues with it in Sunburning when you write about what Xia might think about her weirdest childhood moments being memorialized in ink forever. While I believe that you’re making some of the most challenging and thoughtful auto-bio work and want you to keep pumping out books forever, do you ever get exhausted with it and want to dive into fiction?

KR: I’m not exhausted yet! Life changes and provides new content. Even within auto-bio, there are territories I haven’t entered. I’m attracted to truth and reality more than to anything I’ve invented. A few times I’ve gone into a fictional passage that was contained by my character’s fantasy. I can imagine doing more of that. I find it interesting that fiction writers aren’t often asked if they’re considering switching to auto-biography. When I was a little kid I had one imaginary friend, and only for a short time. It was Robin, of Batman and Robin. My own imaginary friend was a character created by someone else.

More of Keiler’s work can be seen on her website, tumblr, and twitter. There will be a release part for Sunburning, May 20th at Quimby’s. It’s also available for pre-order.

- Bad At Sports Sunday Comics – Lane Milburn - July 9, 2017

- Bad at Sport Sunday Comics- Chicago Alternative Comics Expo Roundup #2 - July 2, 2017

- Bad at Sport Sunday Comics- Chicago Alternative Comics Expo Roundup #1 - June 18, 2017